Black Slaves Beat in Front of Women and Kids

Treatment of Slaves in the United States

Treatment of slaves was characterized by degradation, rape, brutality, and the lack of basic freedoms.

Learning Objectives

Identify methods used to subjugate the enslaved population in the South

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Treatment of slaves varied, but the laws in slaveholding states left enslaved people without defense or recourse in any case.

- Punishment was often meted out in response to disobedience or perceived infractions, but sometimes abuse was carried out simply to reassert the dominance of the master or overseer.

- Slaveholders whipped, shackled, hanged, beat, burned, mutilated, branded, and imprisoned slaves. Slave women were often subject to rape and sexual abuse.

- The offspring of slave women with a man of any race were born into slavery, resulting in a large number of mixed race, or mulatto, slaves. In contrast, many Southern societies strongly prohibited sexual relations between white women and black men in an attempt to maintain"racial purity."

Key Terms

- mulatto: A person of mixed African and Caucasian descent; the term is used in historical contexts, but not in modern culture.

- chattel: Tangible, moveable property. A slave.

General Elements in Slave Treatment

The treatment of slaves in the United States varied widely depending on conditions, time, and place. Generally speaking, urban slaves in the northernmost Southern states had better working conditions and more freedom than their counterparts on Deep South plantations. As slavery became more entrenched and slaves both more numerous and valuable, punishments for infractions increased.

Treatment was generally characterized by brutality, degradation, and inhumanity. Whippings, executions, and rapes were commonplace, and slaves were usually denied educational opportunities, such as learning how to read or write. Medical care was often provided to slaves by the slaveholder's family or fellow slaves who had gleaned medical knowledge via ancestral folk remedies and/or experiences during their time in captivity. After well-known rebellions, such as that by Nat Turner in 1831, some states even prohibited slaves from holding religious gatherings due to the fear that such meetings would facilitate communication and possibly lead to insurrection or escape.

Isolated exceptions existed to the generally horrific institution of slavery. For instance, there were slaves who employed white workers, slave doctors who treated upper-class white patients, and slaves who rented out their labor. Yet these were far from common occurrences.

Sexual Abuses

Slave women in the United States were frequently subjected to rape and sexual abuse. Many slaves fought back against sexual attacks, and many died resisting. Others carried psychological and physical scars from their attacks. Sexual abuse of slave women was rooted in and protected by the patriarchal Southern culture of the era in which all women, black or white, were treated as property, or chattel. As early as the adoption of partus sequitur ventrem into Virginia law in 1662, the children born of sexual relations between any man and a black woman were classified as slaves regardless of the father's race or status. The result after several generations was a large number of mixed race, or mulatto, slaves. At the same time, Southern societies strongly prohibited sexual relations between white women and black men in the name of racial purity.

Maintaining White Dominance

In 1850, a publication provided guidance to slave owners on how to produce the "ideal slave":

- Maintain strict discipline and "unconditional submission";

- Create a sense of personal inferiority, so slaves "know their place";

- Instill fear in the minds of slaves;

- Teach the servants to take interest in the master's enterprise; and

- Ensure that the slave is uneducated, helpless, and dependent by depriving them of access to education and recreation.

Treatment of slaves tended to be harsher on larger plantations, which were often managed by overseers and owned by absentee slaveholders. In contrast, small slave-owning families sometimes provided a more humane environment due to the closer relationship between owners and slaves.

Humane Treatment

Following the prohibition placed on the trans-Atlantic slave trade in the early nineteenth century, some slave owners attempted to improve the living conditions of their existing slaves in order to deter them from running away.

Some proslavery advocates asserted that many slaves were content with their situation. African-American abolitionist J. Sella Martin countered that the apparent contentment was merely a psychological reaction to the exceedingly dehumanizing brutality that some slaves experienced, such as witnessing their spouses sold at auction or seeing their daughters raped.

Education and Access to Information

Slaveholders remained fearful that slaves would rebel or try to escape. Most slaveholders attempted to reduce the risk of rebellion by minimizing the exposure of their slaves to the world beyond their plantation, farm, or workplace, restricting access to information about other slaves and possible rebellions, and degrading the slaves by stifling their ability to exercise their mental faculties. Depriving slaves of such exposure eliminated dreams and aspirations that might arise from an awareness of a larger world.

Education of slaves was generally discouraged (and sometimes prohibited) because it was feared that knowledge—particularly the ability to read and write—would cause slaves to become rebellious. In the mid-nineteenth century, slaving states passed laws making education of slaves illegal. In Virginia in 1841, the punishment for breaking such a law was 20 lashes with a whip to the slave and a fine of $100 to the teacher. In North Carolina in 1841, punishment consisted of 39 lashes to the slave and a fine of $250 to the teacher. Education was not illegal in Kentucky, but it was virtually nonexistent. In Missouri, some slaveholders educated their slaves or permitted the slaves to educate themselves.

Medical Treatment

The quality and extent of medical care received by slaves is not known with much certainty. Some historians speculate that the quality must have been equal to that of white people, assuming owners acted to preserve the value of their property. Others conclude that medical care was poor for slaves, and others suggest that while care provided by slaveholders was neglectful, slaves often provided adequate treatment for one another.

South Carolina plantation slave houses: This image shows slave quarters on a South Carolina plantation.

Slave Codes

Slave codes were laws that were established in each state to define the status of slaves and the rights of their owners.

Learning Objectives

Explain the purpose of slave codes and how they were implemented throughout the United States

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Slaves codes were state laws established to determine the status of slaves and the rights of their owners.

- Slave codes placed harsh restrictions on slaves' already limited freedoms, often in order to preempt rebellion or escape, and gave slave owners absolute power over their slaves.

- Each state's slave codes varied to suit the law of that particular region.

- Some codes prohibited slaves from possessing weapons, leaving their owner's plantations without permission, and lifting a hand against a white person, even in self defense.

Key Terms

- Slave Codes: Slave codes were laws in each U.S. state defining the status of slaves and the rights of their owners and giving slave owners absolute power over their slaves.

Slaves codes were state laws established to regulate the relationship between slave and owner as well as to legitimize the institution of slavery. They were used to determine the status of slaves and the rights of their owners. In practice, these codes placed harsh restrictions on slaves' already limited freedoms and gave slave owners absolute power over their slaves.

African slaves working in seventeenth-century Virginia, by an unknown artist, 1670: Slaves were kept tightly in control through the establishment of slave codes, or laws dictating their status and rights.

Many provisions were designed to control slave populations and preempt rebellion. For example, slaves were prohibited from reading and writing, and owners were mandated to regularly search slave residences for suspicious activity. Some codes prohibited slaves from possessing weapons, leaving their owner's plantations without permission, and lifting a hand against a white person, even in self defense. Occasionally slave codes provided slaves with legal protection in the event of a legal dispute, but only at the discretion of the slave's owner.

It was common for slaves to be prohibited from carrying firearms or learning to read, but there were often important variations in slave codes across states. For example, in Alabama, slaves were not allowed to leave the owner's premises without written consent, nor were they allowed to trade goods among themselves. In Virginia, slaves were not permitted to drink in public within one mile of their master or during public gatherings. In Ohio, an emancipated slave was prohibited from returning to the state in which he or she had been enslaved.

Slave codes in the Northern colonies were less harsh than slave codes in the Southern colonies, but contained many similar provisions. These included forbidding slaves from leaving the owner's land, forbidding whites from selling alcohol to slaves, and specifying punishment for attempting to escape.

Sample Slave Codes

The slave codes of the tobacco colonies (Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia) were modeled on the Virginia code established in 1667. The 1682 Virginia code prohibited slaves from possessing weapons, leaving their owner's plantations without permission, and lifting a hand against a white person, even in self-defense. In addition, a runaway slave refusing to surrender could be killed without penalty.

South Carolina established its slave code in 1712, with the following provisions:

- Slaves were forbidden to leave the owner's property unless they obtained permission or were accompanied by a white person.

- Any slave attempting to run away and leave the colony received the death penalty.

- Any slave who evaded capture for 20 days or more was to be publicly whipped for the first offense; to be branded with the letter "R" on the right cheek for the second offense; to lose one ear if absent for 30 days for the third offense; and to be castrated for the fourth offense.

- Owners refusing to abide by the slave code were fined and forfeited ownership of their slaves.

- Slave homes were searched every two weeks for weapons or stolen goods. Punishment for violations included loss of ears, branding, nose-slitting, and death.

- No slave was allowed to work for pay; plant corn, peas, or rice; keep hogs, cattle, or horses; own or operate a boat; or buy, sell, or wear clothes finer than "Negro cloth."

South Carolina's slave code was revised in 1739 by means of the Negro Act, which included the following amendments:

- No slave could be taught to write, work on Sunday, or work more than 15 hours per day in summer and 14 hours in the winter.

- Willful killing of a slave exacted a fine of 700 pounds, and "passion" killing, 350 pounds.

- The fine for concealing runaway slaves was 1,000 pounds and a prison sentence of up to one year.

- A fine of 100 pounds and six months in prison were imposed for employing any black or slave as a clerk, for selling or giving alcoholic beverages to slaves, and for teaching a slave to read and write.

- Freeing a slave was forbidden, except by deed, and after 1820, only by permission of the legislature.

Regulations for slaves in the District of Columbia, most of whom were servants for the government elite, were in effect until the 1850s. Compared to some Southern codes, the District of Columbia's regulations were relatively moderate. Slaves were allowed to hire their services and live apart from their masters, and free blacks were even allowed to live in the city and operate schools. The code was often used by attorneys and clerks who referred to it when drafting contracts or briefs.

Following the Compromise of 1850, the sale of slaves was outlawed within Washington D.C., and slavery in the District of Columbia ended in 1862 with nearly 3,000 slaveholders being offered a compensation. The district's official printed slave code was issued only a month beforehand.

Free Blacks in the South

Free blacks were an important demographic in the United States, though their rights were often curtailed.

Learning Objectives

Examine the experience of free blacks during the antebellum era

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- In general, as the population of color became larger and more threatening to the white ruling class, governments put increasing restrictions on manumissions and curtailed the rights of free blacks.

- Many free blacks were born free. Others acquired freedom by way of manumission (which could itself occur for a variety of reasons), purchasing their freedom, winning lawsuits for their freedom or escaping.

- By the nineteenth century, families of free blacks who had been free for generations flourished. In the United States, some free blacks achieved a measures of both wealth and societal participation, owning property, paying taxes, publishing newspapers and, in some Northern states, voting.

- Free blacks had restrictions on both their civil and political rights in most states. Property rights were sometimes respected, but also curtailed in some places.

- Free blacks were often hired by the government as rural police, to hunt down runaway slaves and keep order among the slave population.

- By 1776, approximately eight percent of African Americans were free. By 1810, four percent of blacks in the South (10 percent in the Upper South), and 75 percent of blacks in the North were free. On the eve of the Civil War, free blacks comprised about 10 percent of the population.

- When the end of slavery came, the distinction between former slaves and those who had always been "free blacks" persisted in some societies.

Key Terms

- manumission: Release from slavery; freedom.

A "free Negro" (or "free black"), was the term used prior to the abolition of slavery in the United States to describe African Americans who were not slaves. Almost all African Americans came to the United States as slaves, but from the onset of American slavery, slaveholders freed both male and female slaves for various reasons. Sometimes the heirs of deceased slave owners did not want slaves. In other instances, slaves were freed as a reward for good service, and others still were able to pay slaveholders money in exchange for their freedom. Free blacks during the antebellum era—which began with the formation of the Union (1781) and ended with the outbreak of the Civil War (1860)—were very outspoken about the injustice of slavery.

Free blacks in America were first documented in 1662 in Northampton County, Virginia. By 1776, approximately eight percent of African Americans were free.

In the years following the American Revolutionary War (1783–1810), a number of slaveholders in both the North and Upper South, many of whom were inspired by the Revolution's ideals, freed their slaves. Quakers and Moravians in Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware were also influential in persuading slaveholders to free their slaves. In the Upper South, the percentage of free blacks soared from one percent before the Revolution to 10 percent by 1810. By 1860, on the eve of the American Civil War, the nationwide percentage of free blacks remained at 10 percent, but included 45.7 percent of blacks in Maryland, as well as a whopping 91 percent of blacks in Delaware.

Black men enlisted as soldiers and fought in the American Revolution and the War of 1812. Some owned land, homes, and businesses, and paid taxes. In some Northern cities, blacks were even able to vote. Blacks were also outspoken in print, as Freedom's Journal, the first black-owned newspaper, surfaced in 1827. This paper, as well as other early pieces written by blacks, challenged racist conceptions about the intellectual inferiority of African Americans, and added further fuel to the attack on slavery.

Many free African-American families in colonial North Carolina and Virginia became landowners. Ironically, some also became slave owners. Some did so with the intention of protecting family members by purchasing them from their previous owners. Others, however, participated fully in the slave economy. Freedman Cyprian Ricard, for example, purchased an estate in Louisiana that included 100 slaves.

Planters who had mixed-race children sometimes arranged for their children's education (sometimes even in Northern schools) or their employment as apprentices in crafts. Other planters settled property for their children, while others still simply freed their children and their respective mothers altogether. Though fewer in number than in the Upper South, free blacks in the Deep South (especially in Louisiana and Charleston, South Carolina) were also often mixed-race children of wealthy planters. As such, they too had more opportunities to accumulate wealth. Sometimes they were granted transfers of property and social capital. For instance, Wilberforce University, founded in Ohio in 1856 by Methodist and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) representatives for the education of African-American youth, initially received most of its funding from wealthy southern planters who wanted to pay for the education of their mixed-race children.

Many blacks who were elected as either state or local officials during the Reconstruction era in the South had been free in the South prior to the Civil War. Additionally, many educated blacks whose families had long been free in the North moved South to work and help their fellow freedmen.

Notable free people of color include the following:

- Frederick Douglass, an American slave who escaped to the North, earned his education, and led the abolitionist movement in the United States.

- John Swett Rock, born free in New Jersey ca. nineteenth century; worked as a teacher, doctor, lawyer, and abolitionist, and was the first black admitted to the U.S. Supreme Court Bar.

- James Forten, born free in Philadelphia; became a wealthy businessman (sail maker) and strong abolitionist.

- Charles Henry Langston, abolitionist and activist in Ohio and Kansas.

- John Mercer Langston, abolitionist, politician, and activist in Ohio, Virginia, and Washington, D.C.; first dean of Howard University Law Department; first president of Virginia State University; and in 1888, the first black elected to U.S. Congress.

- Robert Purvis, born free in Charleston; became an active abolitionist in Philadelphia, supported the Underground Railroad, and used his inherited wealth to create services for African Americans.

- John Chavis, born free ca. 1762 in North Carolina; was a teacher and a preacher among both white and free blacks until the mid-nineteenth century when laws became stringent.

- Thomas Day, born free ca. 1801 in Virginia; was a famous furniture maker/craftsman in Caswell County, North Carolina.

Freedom's Journal. Freedom's Journal was the first African-American owned and operated newspaper published in the United States.

Freedom's Journal. Freedom's Journal was the first African-American owned and operated newspaper published in the United States.

Skin Color in the South

In many Southern households, the way in which slaves were treated depended on their skin color or on their relation to white individuals in the home.

Learning Objectives

Explain how skin color and the relationship between slave and master shaped the slave community

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Darker-skinned slaves tended to work in the fields, while lighter-skinned slaves tended to work in the house.

- Plantation owners—or " planters "—who had mixed-race children sometimes arranged for their education and training in skilled professions.

- Free blacks in the Deep South were often mixed-race children of planters and were sometimes the recipients of transfers of property and social capital.

Key Terms

- planter: The owner of a plantation.

Many mixed-race families dated back to colonial Virginia, when white women, generally indentured servants, produced children with men of African descent, both slave and free. Because of the mother's status, those children were born free and often married other free people of color.

The belief in racial "purity" drove Southern culture's vehement prohibition of sexual relations between white women and black men, but this same culture essentially protected sexual relations between white men and black women. The result was numerous mixed-race children. The children of white fathers and slave mothers were mixed race slaves whose appearance was generally classified as " mulatto," a term that initially meant a person with white and black parents, but grew to encompass any apparently mixed-race person.

White and black individuals often were linked together in very intimate ways. Many mixed-race house servants were actually related to white members of the household. Often these relationships were the product of unequal power structures and sexual abuse; however, the children resulting from these relationships were sometimes offered greater opportunities for education, skilled professional development, and even freedom and acceptance within white society. In many households, for instance, the way in which slaves were treated depended on the slave's skin color. Darker-skinned slaves worked in the fields while lighter-skinned slaves worked in the house and had comparatively better clothing, food, and housing. Sometimes planters used mixed-race slaves as house servants or favored artisans because they were their own children or the children of their relatives.

Planters who had mixed-race children sometimes arranged for their children's education, even sending them to schools in the North, or securing their employment as apprentices in crafts. In its early years, Wilberforce University, which was founded in Ohio in 1856 for the education of African-American youth, was largely financed by wealthy Southern planters who wanted to provide for the education of their mixed race children. Some planters freed both the children and the mothers of their children.

Though fewer in number than in the Upper South, free blacks in the Deep South (especially in Louisiana and Charleston, South Carolina) were often mixed-race children of wealthy planters and received transfers of property and social capital. Despite their familial connections and freedom, many mixed-race individuals still faced discrimination and prejudice due to the color of their skin.

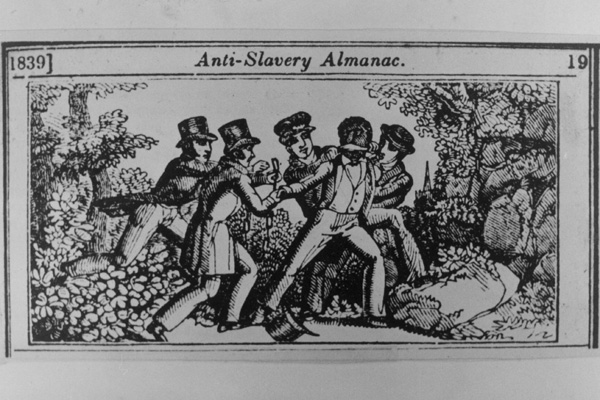

Slave patrol: A woodcut from the abolitionist Anti-Slavery Almanac (1839) depicts a slave patrol capturing a fugitive slave.

Women and Slavery

The sexual abuse of slaves was a common occurrence in the antebellum South.

Learning Objectives

Examine the prevalence of sexual abuse perpetuated by white males against black slaves throughout American history

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Sexual abuse of slaves was partially rooted in a patriarchal Southern culture that perceived all women, whether black or white, as chattel, or property.

- Rape was also used to increase the slave population as a part of the practice of slave breeding, particularly after the 1808 federal ban on the importation of slaves.

- Beginning in 1662, Southern colonies adopted into law the principle ofpartus sequitur ventrem, by which children of slave women took the status of their mother, regardless of the father's identity.

- "Fancy maids" were sold at auction into concubinage or prostitution, which was termed the "fancy trade."

Key Terms

- miscegenation: The interbreeding of individuals considered to be of different racial backgrounds.

- fancy trade: A process by which female slaves called "fancy maids" were sold at auction into concubinage or prostitution.

- slave breeding: A practice of slave ownership in the United States that aimed to encourage the reproduction of slaves in order to increase a slaveholder's property and wealth.

Female Slaves and the Law

Southern rape laws embodied race-based double standards. In the antebellum period, black men accused of rape were punished with death whereas white men could rape or sexually abuse female slaves without fear of punishment. In fact, by the nineteenth century, popular works in the South depicted female slaves as lustful, promiscuous "jezebels" who shamelessly tempted white owners into sexual relations, thereby justifying abuse perpetrated by white men against black women. Children, free women, indentured servants, and black men also endured similar treatment from their masters, or even their masters' children or relatives. While free or white women could charge their perpetrators with rape, slave women had no legal recourse. Their bodies technically belonged to their owners by law. The sexual abuse of slaves was partially rooted in a patriarchal Southern culture that perceived all women, whether black or white, as chattel, or property.

Beginning in 1662, Southern colonies adopted into law the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, by which children of slave women took the status of their mother regardless of the father's identity. This was a departure from English common law, which held that children took their father's status. Some slave-owner fathers freed their children, but many did not. The law relieved men of the responsibility of supporting their children and confined the "secret" of miscegenation to the slave quarters. By 1860, just over 10 percent of the slave population was mulatto.

Slave Breeding

"Slave breeding" refers to those practices of slave ownership that aimed to influence the reproduction of slaves in order to increase the profit and wealth of slaveholders. Such breeding was in part motivated by the 1808 federal ban on the importation of slaves, which was enacted during an intense period of competition in cotton production between the South and the West. Slave breeding involved coerced sexual relations between male and female slaves, as well as sexual relations between a master and his female slaves, with the intention of producing slave children.

Families

Slaveholders owned, controlled, and sold entire families of slaves. Slave owners might decide to sell families or family members for profit, as punishment, or to pay debts. Slaveholders also gave slaves away to grown children or other family members as wedding settlements. They considered slave children ready to work and leave home once they were 12 to 14 years old.

Concubines and Sexual Slaves

Some female slaves called "fancy maids" were sold at auction into concubinage or prostitution, which was termed the "fancy trade." Concubine slaves were the only class of female slaves who sold for higher prices than skilled male slaves.

In the early years of the Louisiana colony, French men took wives and mistresses from among the slaves. They often freed their mixed-race children and sometimes the mistresses themselves. A considerable class of free people of color developed in and around New Orleans and Mobile. By the late 1700s, New Orleans had a relatively formalized system of plaçage among Creoles of color, which continued under Spanish rule. Mothers negotiated settlements or dowries for their daughters to be mistresses to white men. The men sometimes paid for the education of their children, especially their sons, who they sometimes sent to France for schooling and military service.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

Harriet Jacobs documented her experience with sexual abuse in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

Slave Families

Slave codes and slaveholder practices often denied slaves autonomy over their familial relationships.

Learning Objectives

Describe the formation of slave families as presented by John W. Blassingame in his book The Slave Community

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Slave owners sometimes encouraged monogamous relationships among slaves, but often separated couples through sales.

- Parents could not protect their children (or themselves or one another) from being whipped, raped, or sold away.

- Children often observed their fathers acting submissively to slave owners and more autonomously in private.

- Despite restrictions and persecution, the family was a valued source of

support for slaves.

Key Terms

- monogamous: Being married or in a committed relationship to one person at a time.

Slave marriages were illegal in Southern states, and slave couples were frequently separated by slave owners through sale. Often slaves were not even permitted to choose their sexual partners or co-parents. In The Slave Community (1979), historian John W. Blassingame grants that slave owners did have control over slave marriages. They encouraged monogamous relationships to, "make it easier to discipline their slaves…. A black man, they reasoned, who loved his wife and his children was less likely to be rebellious or to run away than would a 'single' slave." Blassingame notes that when a slave couple resided on the same plantation, the husband witnessed the whipping and raping of his wife and the sale of his children. He remarks, "Nothing demonstrated his powerlessness as much as the slave's inability to prevent the forcible sale of his wife and children."

Nevertheless, Blassingame argues that, "however frequently the family was broken it was primarily responsible for the slave's ability to survive on the plantation without becoming totally dependent on and submissive to his master." He contends:

"While the form of family life in the quarters differed radically from that among free Negroes and whites, this does not mean it failed to perform many of the traditional functions of the family—the rearing of children being one of the most important of these functions. Since slave parents were primarily responsible for training their children, they could cushion the shock of bondage for them, help them to understand their situation, teach them values different from those their masters tried to instill in them, and give them a referent for self-esteem other than the master."

Blassingame asserts that slave parents attempted to shield infants and young children from the brutality of the plantation. When children understood that they were enslaved (usually after their first whipping), parents dissuaded the children from trying to run away or seek revenge.

Children observed fathers demonstrating two behavioral types. In the quarters, he "acted like a man," castigating whites for his and his family's mistreatment; in the field working for the master, he appeared obedient and submissive. According to Blassingame, "Sometimes children internalized both the true personality traits and the contradictory behavioral patterns of their parents." He believes that children recognized submissiveness as a convenient method to avoid punishment and the behavior in the quarters as the true behavioral model. Blassingame concludes, "In [the slave father's] family, the slave not only learned how to avoid the blows of the master, but also drew on the love and sympathy of its members to raise his spirits. The family was, in short, an important survival mechanism."

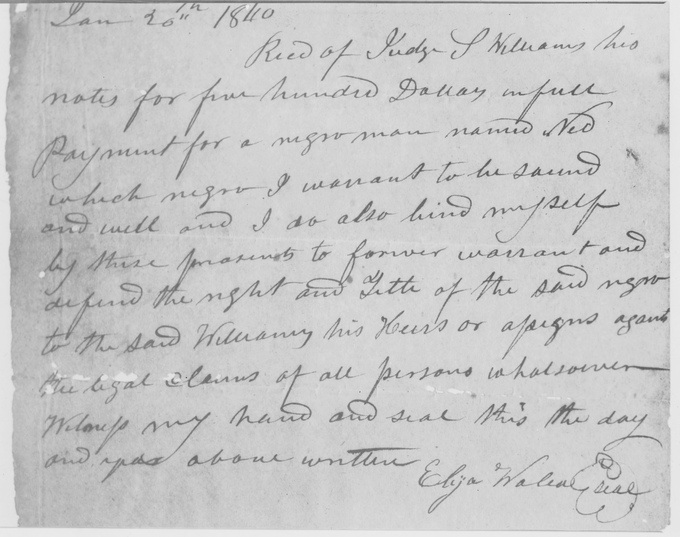

Slave sale receipt: This image shows a receipt for the sale of a slave.

Minstrel Shows

Blackface minstrelsy, which portrayed African Americans in stereotyped, troubling ways, was the first distinctly American theatrical form.

Learning Objectives

Identify the characteristics of a minstrel show

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Minstrel shows were a form of burlesque theater featuring singing and dancing.

- Minstrel shows often were performed by white actors wearing exaggerated black makeup, a practice known as " blackface."

- Minstrel shows purported to depict aspects of African-American culture via song, dance, and instrumental music, but their accuracy is highly dubious.

- Stephen Foster and Daniel Emmett were two popular music composers for minstrel shows.

Key Terms

- blackface: A style of theatrical makeup in which a white person blackens his or her face in order to portray a black person.

- minstrel show: A variety show performed by white people in blackface that portrayed black men as stupid and lazy and black women as rotund and genial.

Blackface Minstrelsy

Blackface minstrelsy was the first distinctly American theatrical form, influencing theater and popular music throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century. In the 1830s and 1840s, it was at the core of a growing American music industry. For several decades it provided the lens through which white America saw black America. On the one hand, it had strong racist overtones; on the other hand, it afforded white Americans a singular and broad awareness of what many considered to be African-American culture.

Minstrel shows originated in the early 1830s as brief burlesques with comic interludes and evolved into a national theatrical art form within the next decade, superseding less accessible genres such as opera for the general populace. The shows typically involved African instruments and dance and featured performers with their faces blackened—a technique called "blackface." One such popular routine was "Jump Jim Crow," a song-and dance routine portraying a caricature of an African American first performed in 1832 by white actor Thomas D. Rice. The routine's popularity gave rise to the term "Jim Crow," a pejorative used to describe African Americans that was co-opted in the 1890s to describe voting laws that enforced racial segregation throughout the South.

Music

Early American popular music consisted of sentimental parlor songs and minstrel-show music, some of which remains in rotation to this day. Popular composers of the era included Stephen Foster and Daniel Emmett. By the middle of the nineteenth century, touring companies had taken minstrel music not only to every part of the United States, but also to the United Kingdom, Western Europe, and even to Africa and Asia. Many minstrel songs and routines were depicted as authentically African American; however, this often was not the case.

Black people had taken part in American popular culture prior to the Civil War era. For instance, the African Grove Theatre in New York City founded in 1821 by freed black man William Alexander Brown was frequented by a large cross-section of black New York society prior to the abolition of slavery in that state. Additionally, Francis Johnson was the first black composer to publish music in 1818. Nonetheless, many of these important artistic advances were made to conform to the prevalent European stylings of the time without taking into account distinctly African cultural contributions.

Loss of Prosperity

By the turn of the twentieth century, the minstrel show enjoyed but a shadow of its former popularity, having been replaced for the most part by vaudeville. It survived as professional entertainment until about 1910, and amateur performances continued until the 1960s in high schools and local theaters. As African Americans began to make advances politically, legally, and socially against racism and prejudicial treatment, minstrelsy lost popularity.

Bryant's Minstrels: An illustration from the playbill for a minstrel show, highlighting singing and dancing by actors in blackface.

Black Slaves Beat in Front of Women and Kids

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-ushistory/chapter/slavery-in-the-u-s/

0 Response to "Black Slaves Beat in Front of Women and Kids"

Post a Comment